एक अनेक बिआपक पूरक जत देखउ तत सोई ॥

माइआ चित्र बचित्र बिमोहित बिरला बूझै कोई ॥

One is in all and all is in One,

Wherever I look there is One

Enchanting is the world of Maya

Only the wise know, they are the only one

सभु गोबिंदु है सभु गोबिंदु है गोबिंद बिनु नही कोई ॥

सूतु एकु मणि सत सहंस जैसे ओति पोति प्रभु सोई ॥

All is Govind,** in all is Govind

Without Govind there is nothing

Like one thread that pierces all beads

God traverses all beings

जल तरंग अरु फेन बुदबुदा जल ते भिंन न होई ॥

इहु परपंचु पारब्रह्म की लीला बिचरत आन न होई ॥

Waves, foam, bubbles from water are not apart

Think and you will see,

the world is an illusion

of the Lord, they are all a play and part

मिथिआ भरमु अरु सुपन मनोरथ सति पदार्थु जानिआ ॥

सुक्रित मनसा गुर उपदेसी जागत ही मनु मानिआ ॥

You desire false illusions and dream objects

Real and true to the mind they appeareth

At Gurus counsel the desire for good deeds

in the a mind awaketh

कहत नामदेउ हरि की रचना देखहु रिदै बीचारी ॥

घट घट अंतरि सरब निरंतरि केवल एक मुरारी ॥

Says Namdev gazing at Lords creation my heart decides

the One and only Murari** in every pore, the Eternal resides

(Namdev’s Bani in Guru Granth Sahib,Ang 485,21934-21941)1

(All English trans. Myself)

Namdeva stands in the company of courageous revolutionary poets like Kabir, Raidas and Nanak, who apart from being saints were also radical reformers who stood above caste and organised religion, broke the bonds of ritual and ceremonies, denounced idolatry and brushed aside the authority of religious scriptures. Being a Shudra, Namdeva had to face the contempt of the Brahmins. He was also one of the pillars of the Warkari movement. He walks among the few in the world who rose from the pits of sin to the realisation of the highest principals of Nirguna bhakti and Advaita

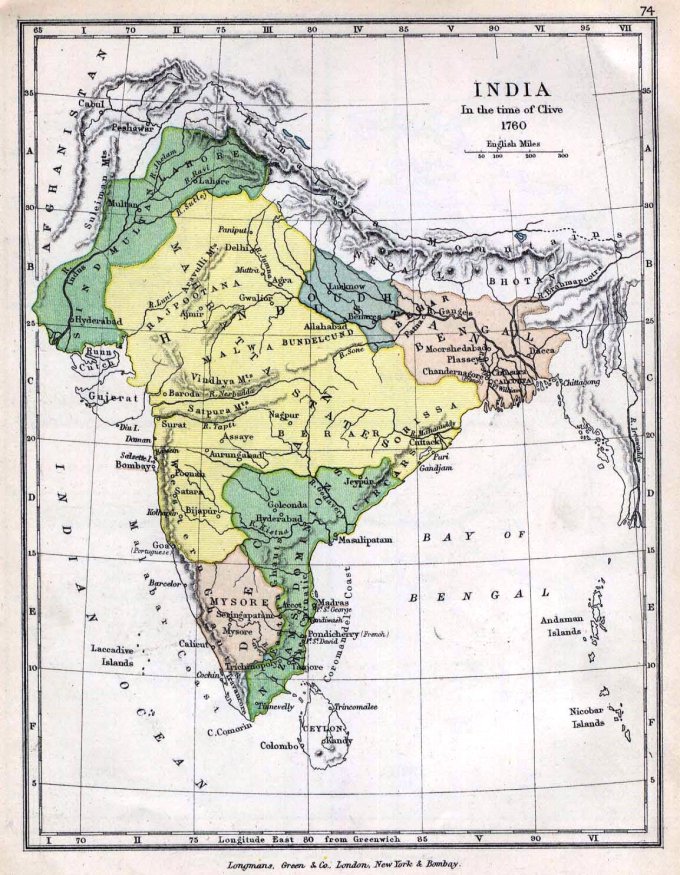

Between the 13th and 17th century a religious and literary renaissance flooded the region of Maharashtra. It was a spiritual awakening, the kind of which was never seen before or after. It scarcely left a soul untouched.

Some even believe that this movement whose basis was Bhakti, which later came to be known as the Warkari movement, was far more powerful than its counterpart in northern and central India. In Maharashtra, this religious revival spanned over 500 years during which more than 50 saints breathed life into it and left their mark. These saints came from all walks of life: Marathas, kunbis, tailors, gardeners, potters, gold smiths, reformed prostitutes and Muslims. 2p45

Sant Namdeva was one of the saints under whose guidance the Warkari movement gathered extraordinary saints in its fold. But apart from being one of the stalwarts of the Warkari movement Namdeva is also known as the first major saint poet of Nirguna Bhakti. A ‘Chimpi’ or variously interpreted as a tailor, dyer-cloth printer by caste, he also stands among those few saints who rose from the pit of evil doers 3p.16;4p.85 to a Saguna bhakti saint and ultimately reached the unfathomable heights of Nirguna bhakti. The sixty one hymns of Namdeva, which are included in the Guru Granth Sahib, pertain to the period when he had achieved enlightenment through devotion to the formless Absolute – Nirguna Bhakti. This change in the nature of his devotion and perception, from being a passionate devotee of Vithoba of Pandharpur to a nirgunibhakta who considered Vithoba to be a symbol of the supreme Soul that pervades the Universe is apparent in his Abhangs. Namadeva’s guru, Shri Visoba Kechar, who himself was a disciple of Gyanadeva, is believed to have shown the path of Nirguna bhakti to Namadeva4p.120. In Namdeva's Abhangs one can see the synthesis of knowledge and devotion.

Namadeva’s contribution to Bhakti literature is significant. Apart from bhajans (devotional songs set to music), he is believed to have written over 2500 abhangs(a form of devotional poetry sung in Marathi in the praise of Vithoba during pilgrimage to the temples of Pandharpur, the centre of Warkari movement) and about 250 padavalis – simple passionate lyrics in Hindi. These padavalis are beautiful syncretic lyrics in which Namadeva used various dialects of northern India that he came across during his travels. These include Khadi boli, Brajabhasha, Purvi Hindi, Punjabi, Arabic and Persian. In these Padvalis we get a glimpse of this saint and his beliefs.

He ridiculed idol worship:

एकै पाथर कीजै भाउ ॥

दूजै पाथर धरीऐ पाउ ॥

जे ओहु देउ त ओहु भी देवा ॥

कहि नामदेउ हम हरि की सेवा ॥४॥१॥

One stone is worshiped while the other is trodden upon

If one is god why the other is not?

Says Namdeva I worship Hari** none other ought

(Namdev’s Bani in Guru Granth Sahib,Ang 525,23502-2194)1

He was of the opinion that saguna bhakti i.e. the worship of God with attributes with its rituals is only a ladder to be discarded once the goal of Nirgun bhakti, the worship and oneness with the Formless Reality is achieved:

तीरथ ब्रत जगत की आस। फोकट कीजै बिन बिसवास।।

एकादसी जगत की करनीं। पाया महल तब तजी निसरनीं।।

भणंत नामदेवतुम्हारै सरणां। मुझा मनवां तुझा चरणां।।2p.283-84,Pad56

In pilgrimages and fast the world’s hope lies

Without true faith useless they lie

The ladder of fasts and outward rituals

Once the divine palace is attained it is of no use

Says Namdev he seeks Your shelter,

my heart lies at your feet’s shelter

He was brutal in his criticism of the hypocrisy and facade among Hindus and Muslims alike:

ब्रह्मा पढ़ि गुंनि बैद सुनावै मन की भ्रांति न जाइ रे

करम करै सौ सूझै नांहीं बहुतक करम कराइ रे

मास दिवस लग रोजा साधै कलमां बंग पुकारैं रे

मन मैं काती जीव बाधारैं नांव अलह का सारैं रे

केवल ब्रह्म सती करि जांनैंसहज सुंनि मैं ध्याया रे

प्रणवंत नांमदेव गुर परसादैं पाया तिनिहीं लुकाया रे 2 Pad 64, p291

They read Brahma, Veda yet deluded they remain

Offer endless rituals yet ignorance they gain

They observe the month long Ramzan fast

by the muezzin a call for prayer is requested

recite the name of Allah

yet with violent minds they are afflicted

Only those who know the One Brahma

can dwell effortlessly in the Formless

To the grace of guru Namdev bows

keeps it hidden he who knows

हिन्दू अन्हा तुरक काणा दुहां ते गिआनी सिआणा

हिन्दू पूजे देहुरा मुसलमाणु मसीत

नामे सोई सेविया जह देहुरा न मसीत 2 pad 208,p.367

The Hindu is blind and the Muslim is half-blind

None has true knowledge

In the temple worships the Hindu, the Muslim in Masjid

Namdev worships Him who is neither in temple nor Masjid

It is obvious from Namdeva’s Padvalis that like, Kabir after him, Namdeva was well versed in the ways of the Sahaj, Nath and Advaita panths:

चंद सूर दोउ समि करि राषौं मन पवन डीढ डांडी

सहजैं सुषमन तारा मंडल इहि बिधि त्रिस्नां षांडी

बैठा रहूं न फिरूं न डोलूं भूषां रहूं न षाऊं

मरूं न जीऊंअहि निसि भूगतौं नहीं आऊं नहीं जांऊं

गगन मंडल मैं रहनी हमारी सहज सुनिं ग्रीह मेला

अंतरधुनि मैं मन बिलमा ऊंकोई जोगी गंमि लहैला

पाती तोड़ि न पूजौं देवा देवलि देव न होई

नांमां कहै मैं हरि की सरना पुनरपि जनम न होई 2p.292.Pad 65

The sky resounds with the music of the flute

The sound of Anhad every where

Ignorant of his Self, O Lord, the fool wanders

here and there, nowhere

United the Sun and the Moon with ease

Held firm the mind the breath and the spine

Rose I through the subtle to the star constellation

Thereby all desires I cease

Neither stay still nor move nor vacillate I

Neither hungry nor satiated am I

Neither live nor die nor suffer do I

Neither come or go

My home I have made in the cosmic skies

Dwell I effortlessly in the Void within

Enrapt is my mind with the music within

Rare is a Yogi who can hear such a hymn

I gather no leaves for the Deva in the temple

No God dwells in the idol

Only in Hari, in Hari I have lain

Never to be born again

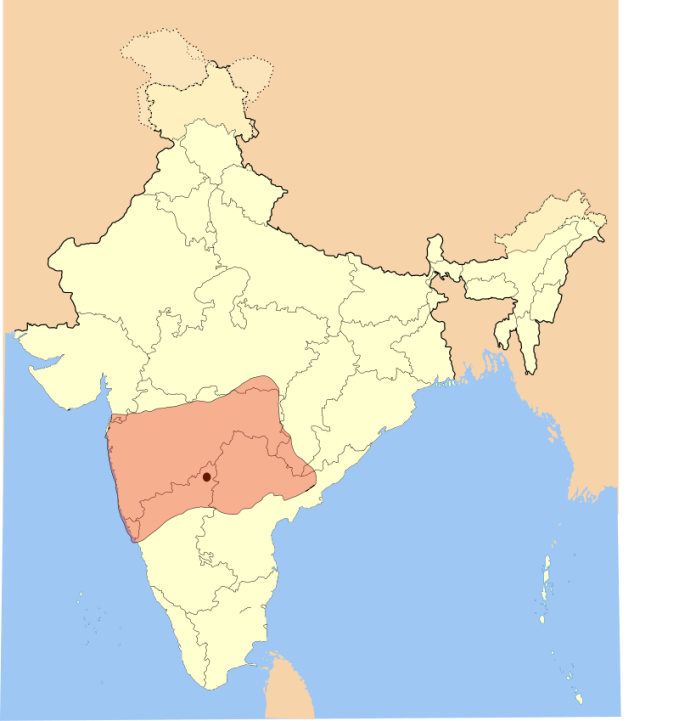

According to the tradition available, Namdeva (1270-1350) was a close companion of Sant Jnanesvar also known as Gyanadeva, another great Marathi saint and the author of Gyaneshvari.2p.43 Namdeva was a householder and a married man. After Gyanadeva’s death, Namdeva moved to north India and settled in Punjab in a village called Ghuman in Gurdaspur. Here he spent 20 years of his life spreading the message of devotion. However, some scholars question whether Namdev was a contemporary of Gyanadeva and whether the two came in contact with each other at all3p18.

While Gyanadeva’s influence was limited to Maharashtra, Namdeva along with Ramananda*** spread a more evolved form of Bhakti in North and Central India and laid ground for future Nirguna saint poets like Kabir, Nanak and Raidas.

Notes

*All English translations of the poetic compositions are by the author, Rupa Abdi

** Govind, Hari, Murari, Ram etc. are various names, avatars and attributes of Vishnu, however in case of Namdeva, they are the various names by which he addressed the Ultimate Reality.

***A 14

th century Bhakti saint who founded a new school of Vaishnavism based on love and devotion

References and further reading:

- https://www.searchgurbani.com/

- Sadarangani N.M. 2004.Bhakti Poetry in Medieval India: Its Inception, Cultural Encounter and Impact. Sarup and Sons. New Delhi

- MacNicole, N.1919.The Heritage of India: Psalms of Maratha Saints. Association Press. Calcutta

- S.K. 1972. हिंदी निर्गुणी काव्य का प्रारम्भ और नामदेवकी हिन्दी कविता. Rachana Prakashan. Allahabad

- Callewaert, Winand M & Mukund Lath. 1989. The Hindi Padavali of Namdev. Motilal Banarasidass Publishers Pvt.Ltd. Delhi