While we Indians pride ourselves over the rich diversity of communities, race and religion that our country has, it also means dealing with differences and contradictions in the way we live, eat and pray. However there has always been a sense of, not just tolerance, but respect for these differences. This appears to be an intrinsic factor of Indian cultural ethos. Mahatma Gandhi once said, ‘we must respect other religions, as we respect our own. Mere tolerance is not enough’. There have been times when this sentiment could not hold up against hatered and violence however there were other times too when this sentiment flowered against heavy odds. Seventeenth century Maratha society was one such period in the history of this great nation.

It is a myth to presume that a society at confrontation with itself cannot find ways to co-exist peacefully. The Medieval period in the Maratha Empire saw three apparently conflicting forces at work, especially during the seventeenth century: there was religious as well as political conflicts among the Bahamani kingdom, the Mughals and the Marathas. With the consolidation of Maratha power in this century, the Hindu and Muslim communities of the Maratha society found innovative ways of co-existing with mutual respect and peaceful tolerance. There were instances of hate and intolerance, no doubt, but these were offset by numerous examples to the contrary. The people and the rulers, in their wisdom knew that the only way for a peaceful society was respecting and giving space to the ‘other religion’. Marathi writers and historian have cited numerous instances of this as depicted in the daily lives of administrators and rulers. Examples from which our present day society could learn a lesson or two.

- Bahmani Sultanate 1347-1527 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Saraswati Gangadhar, author of Gurucharitra, a poetic work of the fourteenth century, mentions that Alauddin II (1435-57), of the Bahamani dynasty which ruled over much of Deccan India, including parts of present day Maharashtra between the 13th and 16th century, held great respect for Narsimha Saraswati, the hero of Gurucharitra.

Ibrahim Adil Shah II (1490-1510) another Bahmani ruler, tried to create cultural harmony among Shias, Sunnis and Hindus through the medium of Art. According to Chitnis (p48) he was a worshipper of Allah and a Hindu goddess. Both the Mandir and the Masjid were sacred to him. His official documents would begin with the words Az-puja-i Shri Saraswati. He built a temple at Bijapur dedicated to Lord Narsimha. He bestowed liberal grants to temples and safeguarded the rights of pujaris. Little wonder that he came to be known as Jagadguru.

The Mahanbhav Matha of Otur (Pune) received land grants from the Nizam Shahi rulers who ruled over large parts of Deccan (1490-1633) with their capital at Ahmednagar in present day Maharashtra. Chand bibi, the regent of Ahmednagar (1596-99) and sister of Hussain Nizam Shah I, sent a note to her officers to respect all such grants to Hindus and Brahmans. The priest of Pedgaon (Ahmednagar) too received land grant from Malik Amber (1549-1626) who was a very popular Siddi Prime Minister in the Ahmednagar Sultanate (Kulkarni p. 113).

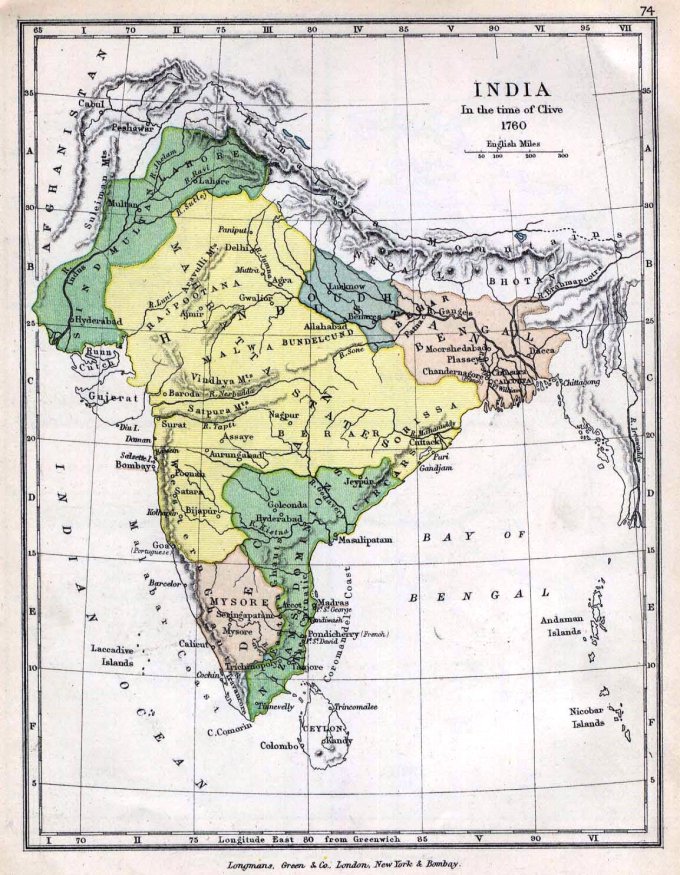

- Maratha Empire 1674-1818 (photo credit: Wikipedia)

Among the rulers of the Maratha Empire (1674-1818), Shivaji’s grandfather, Maloji Bhonsale was a disciple of the legendary Muslim saint-poet, Shaikh Muhammad, and when Maloji shifted to Nizamshahi (in Ahmednagar district) he brought Shaikh Muhammad along with him (Kulkarni p.110). Maloji also gave 12 bigha land to Shaikh Muhammad and built a math (hermitage) for him at Shrigonde (Dhere, p60). Ramdas, the great saint poet of 17th century, was a strong critic of the Muslim rule but a great admirer of Shaikh Muhammad (Chitnis, p110). Sant Ramdas was Shivaji’s guru.

Maloji Bhaonsale’s wife and Shivaji’s grandmother, Umabai, took a vow to Shah Sharif of Ahmednagar for a child and when she gave birth to two sons, they were named after this Pir : Shahaji and Sharifji, in gratitude for his blessings (Dhere, p.60). The dargah of Shah Sharif enjoyed two villages, Eklare and Konosi under the Marathas (Bendre). Mir Sayyid Sadi of Nasik and Mulla Hussaini Mosque of Rannebennur (Dharwad) received inam lands from Shahaji (Kulkarni p. 112). Shivaji held great respect for Baba Yakut of Utambar village near Kelashi (Ratnagiri) and Sambhaji undertook the construction of his dargah which eventually remained incomplete. Numerous Muslim holy men received allowances for maintenance and illumination of mosques from Shivaji, including the Pir of Sayyid Sadat Hazrat (Pune region). The Kazi of Indapur and the khidmatgar of the Bhambavade mosque received land and allowances from Shivaji. Many believe that Shivaji’s son, Sambhaji was victorious against the Portuguese due to the blessings of Pir Abdullah Khan and in return the Prime Minsiter, Kavi Kailash granted the Pir certain allowances. Shivaji’s grandson, Shahuji gave an entire village in grant to the Muslim saint Sayyid Ata-ullah of Shakarkoti of Loni in Pune. The Peshwas too were equally generous and benevolent towards Muslim holy men: Pirs Sayyid Sada and Shaikh Salah received grants from Peshwas for construction purposes. Even the dispute among them regarding who would lead the Muharram procession was settled by the Peshwas. Dargah of Shaikh Salah and Takiya of Angad Shah received one sher of rice and one paisa for Frankincense every day from the royal palace.

The village councils were called gotsabhas and enjoyed supreme positon in the society and state and it decided cases that effected the whole society. The Kazi and the Maulana had a seat in the gotsabha and in every village Got, the proportion of Muslim members was usually proportional to the Muslim population in that village. Both the Hindus and Muslims sat together in the temple village and settled disputes irrespective of caste or religion. Mulansara, a kind of tax originally introduced by the Muslim rulers for the maintenance of the village Maulana continued under the Marathas. Muslim Patils were not unheard of under the Marathas (Kulkarni p.115).

Both the Bhakti and Sufi movements were at their peak during this period, both sought to bring about socio-religious reforms in their communities. With their message of universal love and brotherhood, they placed the service of fellow humans above religious rituals. Muslims learnt Sanskrit and also studied the sacred poetry of Bhakti saints. The study of the ‘other’ religion promoted a better understanding of each other and helped in eradication of religious prejudices. The well-known Marathi saint poet of this period, Sant Eknath wrote his famous gatha – Hindu Turk Samvad which consisted of a dialogue between a Hindu and a Muslim (Turk) who, at the end of a lengthy dialogue, end up respecting each other as creations of Khuda. Sufis at this time made valuable contributions to devotional literature in Marathi. Shaikh Muhammad, the Muslim saint poet wrote Yoga Sangram (1645), Nishkalanka Prabodh, Pavan Vijaya and 300 abhangas (devotional poetry sung in the praise of the Lord Vitthal) in Marathi. Another Muslim saint of this period, Husain Ambakhan, who was a devotee of Lord Ganesh, wrote a Marathi commentary on the Bhagvatgita. Shah Muntoji Bhahmani, a Muslim saint of the seventeenth century, who hailed from the royal family of Bidar (Bahmani Rulers) was initiated into the Bhakti cult by a Hindu saint – Sahajanand Swami of Kalyan (Bijapur). Shah Muntoji wrote Panchikaran in Dakhani Hindi, outlining the common fundamental concepts in Hindu and Muslim scriptures. His contemporary, Shah Muni, a Muslim saint, lamented that the enmity between Hindus and Muslims was due to the absence of proper understanding of their respective faiths (Kulkarni p.111).

Time and again the people, the mystics and the leaders have proved that the essence of this land is peace and harmony in spite of differences and diversity. Let us sow the seeds of love again in the consciousness of this sub-continent.

References and Extra Reading:

- Bendre, V S. Ed. Maharashtr etihasachi Sadhane, vols.1-3: part II vol II: 314,315

- Chitnis, Krishnaji Nageshrao.2003. Medieval Indian History. Atlantic Publishers and Distributes. New Delhi

- Dhere, R C. 1967. Musalman Marathi Sant Kavi. Padyagandha Prakashan. Pune.

- Kularni A R. 1999. Social Relations in Medieval Maharashtra: Experiments in Living Together. In: We Lived Together. Eds. S Settar and P K V Kaimal. 1999. Pragati Publications. Delhi

- Parasnis, D B (ed.). 1917. Peshwe Daftaratil Sanadpatratil Mahiti, Bombay

- Potdar, D V. (Introduction) Aitihasik Samkeerna Sahitya, BISM Publication, Pune vol. 8 (ASS Vol.)

- Rajwade, V K (ed.). 1908. Marathyanchya Itihasachi Sadhane. Vol.15. Kolhapur.

- Shivacharitra Sahitya, 1930.vol.II. 94. Bharat Itihas Samshodhak Mandal, Dutto Waman Potdar, Pune